Armitage on the American Bible Union Versions

From Thomas Armitage, A History of the Baptists; Traced by their Vital Principles and Practices, from the Time of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ to the Year 1886 (New York: Bryan, Taylor, & Co., 1887), pp. 893-918

CHAPTER XVII. BIBLE TRANSLATION AND BIBLE SOCIETIES.

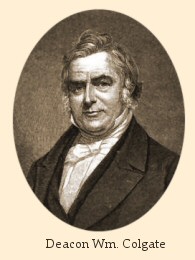

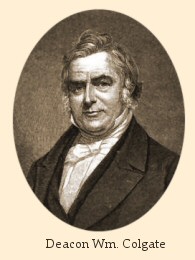

Early in the Nineteenth Century, local Bible Societies sprang up in various American towns and cities. So far as is known, the first of these was formed in Philadelphia, in December, 1808, primarily under the wisdom and zeal of Dr. Staughton, who was its first recording secretary and wrote its appeals for aid. In February, 1809, a similar society was organized in New York, called the 'Young Men's Bible Society,' and on this wise. William Colgate, a young Englishman, sacredly cherished a Bible which had been presented to him by his father, which was kept in his pew in the First Baptist meeting-house; but it was stolen, and thinking that Bibles must be very scarce or they would not be taken by theft, he conversed with others, and they resolved to form a society to meet the want. This society comprehended the purpose of translation as well as of circulation, and incorporated the following into its Constitution as its defining article:

'The object of this Society is to distribute the Bible only—and that without notes—amongst such persons as may not be able to purchase it; and also, as far as may be practicable, to translate or assist in causing it to be translated into other languages.'

Soon other societies were formed in different places, and the universal want of a General Society began to be felt. At length, May 11, 1816, thirty-five local societies in different parts of the country sent delegates to a Bible Convention which assembled in New York, and organized the American Bible Society for 'The dissemination of the Scriptures in the received versions where they exist, and in the most faithful where they may be required.' Most of the local societies either disbanded or were made auxilliary to the General Society. The Baptists became at once its earnest and liberal supporters. As early as 1830 it made an appropriation of $1,200 for Judson's 'Burman Bible,' through the Baptist Triennial Convention, with the full knowledge that he had translated the family of words relating to baptism by words which meant immerse and immersion, and down to 1835 the Society had appropriated $18,500 for the same purpose. The Triennial Convention had instructed its missionaries in April, 1833, thus:

'Resolved, That the Board feel it to be their duty to adopt all prudent measures to give to the heathen the pure word of God in their own languages, and to furnish their missionaries with all the means in their power to make their translation as exact a representation of the mind of the Holy Spirit as may be possible.'

'Resolved, That all the missionaries of the Board who are, or who shall be, engaged in translating the Scriptures, be instructed to endeavor, by earnest prayer and diligent study, to ascertain the precise meaning of the original text, to express that meaning as exactly as the nature of the languages into which they shall translate the Bible will permit, and to transfer no words which are capable of being literally translated.'

In 1835 Mr. Pearce asked the Society to aid in printing the 'Bengali New Testament,' which was translated upon the same principle as Judson's Bible. The committee which considered the application reported as follows: 'That the committee do not deem it expedient to recommend an appropriation, until the Board settle a principle in relation to the Greek word baptizo.' Then the whole subject was referred to a committee of seven, who, November 19, 1835, presented the following reports:

'The Committee to whom was recommitted the determining of a principle upon which the American Bible Society will aid in printing and distributing the Bible in foreign languages, beg leave to report,

'That they are of the opinion that it is expedient to withdraw their former report on the particular case, and to present the following one on the general principle:

'By the Constitution of the American Bible Society, its Managers are, in the circulation of the Holy Scriptures, restricted to such copies as are without note or comment, and in the English language, to the version in common use. The design of these restrictions clearly seems to have been to simplify and mark out the duties of the Society; so that all the religious denominations of which it is composed might harmoniously unite in performing those duties.

'As the Managers are now called to aid extensively in circulating the Sacred Scriptures in languages other than the English, they deem it their duty, in conformity with the obvious spirit of their compact, to adopt the following resolution as the rule of their conduct in making appropriations for the circulation of the Scriptures in all foreign tongues:

Resolved, 1. That in appropriating money for the translating, printing or distributing of the Sacred Scriptures in Foreign languages, the Managers feel at liberty to encourage only such versions as conform in the principle of their translation to the common English version, at least so far as that all the religious denominations represented in this Society, can consistently use and circulate said versions in their several schools and communities.

'Resolved, 2. That a copy of the above preamble and resolution be sent to each of the Missionary Boards accustomed to receive pecuniary grants from the Society, with a request that the same may be transmitted to their respective mission stations, where the Scriptures are in process of translation, and also that the several Mission Boards be informed that their application for aid must be accompanied with a declaration that the versions which they propose to circulate are executed in accordance with the above resolution.

THOMAS MACAULEY; Chairman, WM. H. VANVLECK, JAMES MILNOR, FRANCIS HALL, THOMAS DEWITT, THOMAS COCK.'

COUNTER REPORT.

'The subscriber, as a member of the Committee to whom was referred the application of Messrs. Pearce and Yates, for aid in the circulation of the Bengali New Testament, begs leave to submit the following considerations:

'1. The Baptist Board of Foreign Missions have not been under the impression that the American Bible Society was organized upon the central principle that baptizo and its cognates were never to be translated, but always transferred, in all versions of the Scriptures patronized by them. Had this principle been candidly stated and uniformly acted upon by the Society in the appropriation of its funds for foreign distribution, the Baptists never could have been guilty of the folly or duplicity of soliciting aid for translations made by their missionaries.

'2. As there is now a large balance in the treasury of the American Bible Society, as many liberal bequests and donations have been made by Baptists, and as these were made in the full confidence that the Society could constitutionally assist their own denomination, as well as the other evangelical denominations comprising the Institution, in giving the Bible to the heathen world, therefore,

'Resolved, That $——— be appropriated and paid to the Baptist General Convention of the United States for Foreign Missions, to aid them in the work of supplying the perishing millions of the East with the Sacred Scriptures.

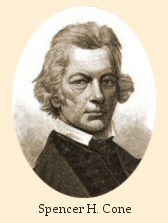

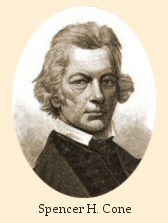

SPENCER H. CONE.'

It must stand to the everlasting honor of the Triennial Convention that they regarded the Author of the Bible as the only being to be consulted in this matter. They disallowed any voice to the translator in making his translation, but virtually said to him: 'The parchment which you hold in your hand is God's word, all that you have to do is to re-utter the Divine voice. The right of Jehovah to a hearing as he will is the only consideration in this case. You are to inquire of him by earnest prayer, you are to use the most diligent study to ascertain the precise meaning of the original text, then you are to make your translation as exact a representation of the mind of the Holy Spirit as may be possible, so far as the nature of the language into which you translate will permit.' In contrast with this, the Bible Society said: 'You are to take the common English version and conform your version to the principle on which it was made, so that all "denominations represented in this Society can use it in their schools and communities."' A version, and that quite imperfect, was to be made the standard by which all versions should be made, and the voice of all the denominations in the Society was to be consulted instead of the mind of the Holy Spirit. Such an untenable position settled the question of further co-operation with the Society in the making and circulation of foreign versions, for a more dangerous position could not be taken. Up to that time, including a large legacy which John F. Marsh had made, the Baptists had contributed to the treasury of the Bible Society at least $170,000, and had received for their missionary versions less than $30,000.

On May 12, 1836, the Bible Society approved the attitude of its Board, and $5,000 was voted for the versions made by the Baptist missionaries to be used on the new principle which had been adopted. The Baptist members of the Board presented a clear, calm and dignified Protest, but were not allowed even to read it to the Board. Amongst many other grave considerations they submitted these: 'The Baptists cannot, consistently with their religious principles, in any case where they are permitted to choose, consent to use or circulate any version in which any important portion of divine truth is concealed or obscured, either by non-translation or by ambiguity of expression. . . . This resolution exposes the Society, almost unavoidably, to the charge or suspicion of sectarian motives. For, without pretending, in the least, to impeach the accuracy of the versions against which it is directed, the principal reason offered by its advocates when urging its adoption was, "That Pedobaptists might have an opportunity of prosecuting their missionary operations without let or hinderance, where the translations of the Baptists are in circulation." And surely, a version that purposely withholds the truth, either by non-translation or by ambiguity of expression, for the sake of accommodating Pedobaptists, is as really sectarian as one that adds to the truth from the same motive. . . . The imperfection and injustice of the resolution are strikingly manifested in the continued circulation of Roman Catholic versions, which are neither conformed in the principle of their translation to the common English version, nor can they be consistently used by the different denominations represented in the American Bible Society. They are characterized by the numerous absurd and heretical dogmas of the Catholic sect, and yet the rule in question cordially approves of their extensive distribution, while the translations of pious, faithful and learned Baptist ministers are rejected.'

The Board of the Triennial Convention met at Hartford, Conn., on the 7th of April, 1836, and at once 'respectfully informed' the Board of the American Bible Society that they could not 'consistently and conscientiously comply with the conditions' on which their appropriation was made, and that they could not, 'therefore, accept the sum appropriated.' Here, then, the sharp issue was drawn between the question of denominational 'use' and 'the mind of the Holy Spirit,' in the holy work of Bible translation. Not only was the Baptist position sustained, but the manly and Christian stand taken by its representatives in the Board was approved by our Churches, and an almost unanimous determination was readied to support the faithful versions made by our missionaries. Action was taken in Churches, associations and conventions, and an almost universal demand was made for a new Bible Society. Powerful pens were also wielded outside the Baptist body to defend their course, amongst them that of the late Joshua Leavitt, a distinguished Congregationalist, who said:

'The Baptist Board had instructed their missionaries on the subject, "to make their translations as exact a representation of the mind of the Holy Spirit as may be possible;" and "to transfer no words which are capable of being literally translated." This instruction was a transcript of the principle which underlies the Baptist Churches, to wit, in settled and conscientious belief that the word baptizo means "immerse" and nothing else. It was plainly impossible that Baptist missionaries should honestly translate in any other way. Then the debate turned, in effect, upon the question whether the Bible Society should recognize such men as Judson and his associates as trustworthy translators of the word of God for a people who had been taught the Gospel by them, and for whose use there was, and could be, no other version. . . . The effect of the resolution was to make the Bible Society, in its actual administration, a Pedobaptist or sectarian institution. It was a virtual exclusion of the Baptists from their past rights as the equal associates of their brethren by the solemn compact of the constitution. It left them no alternative but to withdraw, and take measures of their own to supply the millions of Burma with the Scriptures in the only version which could be had, and the only one which they would receive. It was a public exemplification of bad faith in adherence to the constitution of a religious benevolent society. That it attracted so little public attention at the time must be attributed to the general absorption of the public mind with other pursuits and questions and, more than all, to the fact that it was a minority which suffered injustice, while a large majority were more gratified than otherwise at their discomfiture. But the greatest injury was done to the cause of Christian union and to the unity of the Protestant hosts in the conflict with Rome. And this evil is now just about to develop itself in its full extent. The Bible Society, in its original construction, and by its natural and proper influence, ought to be able to present itself before all the world as the representative and exponent of the Protestantism of this nation, instead of which it is only the instrument of sectarian exclusiveness and injustice. One of the largest, most zealous and evangelical and highly progressive Protestant bodies is cut off and set aside, and the Society stands before the world as a one-sided thing, and capable of persistent injustice in favor of a denominational dogma.

'This publication is made under the influence of a strong belief of the imperative necessity which now presses upon us to RIGHT THIS WRONG, that we may be prepared for the grand enterprise, the earnest efforts, the glorious results for the kingdom of Christ, which are just opening before us. We must close up our ranks, we-must reunite all hearts and all hands, in the only way possible, by falling back upon the original constitution of the Society, in letter and spirit, BY THE SIMPLE REPEAL OF THE RESOLUTION.'

Many Baptists from various parts of the country attended the annual meeting of the Bible Society in New York, on the 12th of May, 1836, and when it deliberately adopted the policy of the board as its own permanent plan, about 120 of these held a meeting for deliberation on the 13th, in the Oliver Street Baptist meeting-house, with Dr. Nathaniel Kendrick in the chair. The Baptist Board of Foreign Missions, which met at Hartford, April 27th, had anticipated the possible result, and resolved that in this event it would 'be the duty of the Baptist denomination in the United States to form a distinct organization for Bible translation and distribution in foreign tongues,' and had resolved on the need of a Convention of Churches, at Philadelphia, in April, 1837, 'to adopt such measures as circumstances, in the providence of God may require.' But the meeting in Oliver Street thought it wise to form a new Bible Society at once, and on that day organized the American and Foreign Bible Society provisionally, subject to the decision of the Convention to be held in Philadelphia. This society was formed 'to promote a wider circulation of the Holy Scriptures, in the most faithful versions that can be procured.' In three months it sent $13,000 for the circulation of Asiatic Scriptures, and moved forward with great enthusiasm.

After a year's deliberation the great Bible Convention met in the meetinghouse of the First Baptist Church, Philadelphia, April 26th, 1837. It consisted of 390 members, sent from Churches, Associations, State Conventions, Education Societies and other bodies, in twenty-three States and in the District of Columbia. Rev. Charles Gr. Sommers, Lucius Bolles and Jonathan Going, the committee on 'credentials.' reported that 'in nearly all the letters and minutes where particular instructions are given to the delegates, your committee find a very decided sentiment in favor of a distinct and unfettered organization for Bible translation and distribution.' The official record says that the business of the Convention was 'to consider and decide upon the duty of the denomination, in existing circumstances, respecting the translation and distribution of the sacred Scriptures. Rufus Babcock, of Pennsylvania, was chosen president of the body; with Abiel Sherwood, of Georgia, and Baron Stow, of Massachusetts, as secretaries. Amongst its members there were present: From Maine, John S. Maginnis; New Hampshire, E. E. Cummings; Vermont, Elijah Hutchinson; Massachusetts, George B. Ide, Heman Lincoln, Daniel Sharp, Wm. Hague and James D. Knowles; and from Rhode Island, Francis Wayland, David Benedict and John Blain. Connecticut sent James L. Hodge, Rollin H. Neale, Irah Chase and Lucius Bolles. From New York we have Charles G. Sommers, Wm. Colgate, Edward Kingsford, Alexander M. Beebee, Daniel Haskall, Nathaniel Kendrick, John Peck, Wm. R. Williams, Wm. Parkinson, Duncan Dunbar, Spencer H. Cone, John Dowling and B. T. Welch. New Jersey was represented by Samuel Aaron, Thomas Swaim, Daniel Dodge, Peter P. Runyon, Simon J. Drake, M. J. Rhees and Charles J. Hopkins. Pennsylvania sent Horatio G. Jones, Joseph Taylor, Wm. T. Brantly, J. H. Kennard, J. M. Linnard, Wm. Shadrach, A. D. Gillette and Rufus Babcock. Then from Maryland we find Wm. Crane and Stephen P. Hill; and from Virginia, Thomas Hume, J. B. Taylor, J. B. Jeter and Thomas D. Toy. These were there, with others of equal weight of character and name.

When such momentous issues were pending, our fathers found themselves differing widely in opinion. Some thought a new Bible Society indispensable; others deprecated such a step; some wished to confine the work of the new society to foreign versions; others thought not only that its work should be unrestricted as to field, but that consistency and fidelity to God required it to apply to the English and all other versions the principle which was to be applied to versions in heathen lands, thus making it faithful to God's truth for all lands. The discussion ran through three days, and was participated in by the ablest minds of the denomination, being specially keen, searching and thorough. Professor Knowles says:

'Much feeling was occasionally exhibited, and some undesirable remarks were made. But, with little exception, an excellent spirit reigned throughout the meeting. It was, we believe, the largest and most intelligent assembly of Baptist ministers and laymen that has ever been held. There was a display of talent, eloquence and piety which, we venture to say, no other ecclesiastical body in our country could surpass. Our own estimate of the ability and sound principles of our brethren was greatly elevated. We saw, too, increased evidence that our Churches were firmly united. While there was an independence of opinion which was worthy of Christians and freemen, there was a kind spirit of conciliation. Each man who spoke declared his views with entire frankness; but when the question was taken, the vast body of delegates voted almost in solid column. They all, we believe, with a few exceptions, are satisfied with the results of the meeting as far as regards the present position of the society. The question respecting the range of its operations remains to be decided. We hope that it will be discussed in a calm and fraternal spirit. Let each man be willing to hear his brother's opinion, and to yield his own wishes to those of the majority. We see no reason why any one should be pertinacious. If it should be determined to give to the society an unrestricted range, no man will be obliged to sustain it unless he choose. He who may still prefer to send his money to the American Bible Society can do so. Let us maintain peace among ourselves. Our own union is of more importance than any particular measures which we could adopt, no benefits which would ensue from the operations of any society would compensate for the loss of harmony in our Churches.'

So far the words of Prof. Knowles. The final decisions of this great Convention are found in the following resolutions, which it adopted 'almost in solid column;' namely:

'1. Resolved, That under existing circumstances it is the indispensable duty of the Baptist denomination in the United States to organize a distinct society for the purpose of aiding in the translation, printing and circulation of the sacred Scriptures.

'2. Resolved, That this organization be known by the name of the American and Foreign Bible Society.

'3. Resolved, That the society confine its efforts during the ensuing year to the circulation of the Word of God in foreign tongues.

'4. Resolved, That the Baptist denomination in the United States be affectionately requested to send to the Society, at its annual meeting during the last week 'in April, 1838, their views as to the duty of the Society to engage in the work of home distribution.

'5. Resolved. That a committee of one from each State and district represented in this convention be appointed to draft a constitution and nominate a board of officers for the ensuing year.'

A constitution was then adopted and officers chosen by the Convention itself. It elected Spencer H. Cone for President, Charles G. Sommers for Corresponding Secretary, William Colgate for Treasurer and John West for Recording Secretary; together with thirty-six managers, who, according to the eighth article of the constitution, were 'brethren in good standing in Baptist Churches.'

The convention also instructed its officers to issue a circular to the Baptist Churches throughout the United States, commending its work to their co-operation and confidence, and especially soliciting them to send to the new Society an expression of their wishes as to its duty in the matter of home circulation. This request was very generally complied with, and so earnest was the wish to make it a 'society for the world,' that at its annual meeting in 1838 its constitution was so amended as to read: 'It shall be the object of this Society to aid in the wider circulation of the Holy Scriptures in all lands.' Thus the Baptists took the high and holy ground that they were called to conserve fidelity to God in translating the Bible, and that if they failed to do this on principle, they would fail to honor him altogether in this matter; because the Society which they had founded was the only Bible organization then established which had no fellowship with compromises in Bible translation.

From the first, many in the new Society, led by Dr. Cone, desired to proceed at once to a revision of the English Scriptures, under the guidance of the principles applied to the Asiatic versions made by the Baptist missionaries. But in deference to the opposition of some who approved of the Society in all other respects, at its annual meeting in 1838 it 'Resolved, That in the distribution of the Scriptures in the English language, they will use the commonly received version until otherwise directed by the Society.' Whatever difference of opinion existed amongst the founders of that Society about the immediate expediency of applying the principle of its constitution to the English version, its ultimate application became but a question of time, and this action was postponed for fourteen years. Meanwhile, this measure was pressed in various directions, in addresses at its anniversaries, in essays published by various persons, and in the Society's correspondence. In 1842 Rev. Messrs. David Bernard and Samuel Aaron issued a very able treatise on the need of 'Revising and Amending King James' Version of the Holy Scriptures.' They also procured and published in that year, through the publishing house of J. B. Lippincott, of Philadelphia, a revised version of the Old and New Testaments, 'carefully revised and amended by several Biblical scholars.' This they say they did 'in accordance with the advice of many distinguished brethren, the services of a number of professors, some of whom rank among the first in our country for their knowledge of the original languages and Biblical interpretation and criticism, have been secured to prepare this work.' Amongst these were the late Prof. Whiting, Prof. A. C. Kendrick and other leading scholars who still live and have labored on other revisions.

The American and Foreign Bible Society held its annual meeting in New York May 11th, 1849, and, on the motion of Hon. Isaac Davis, of Massachusetts, after considerable discussion, it was 'Resolved, That the restriction laid by the Society upon the Board of Managers in 1838, to use only the commonly received version in the distribution of the Scriptures in the English language, be removed.' This restriction being removed, the new board referred the question of revision to a committee of five. After long consideration that committee presented three reports: one with three signatures and two minority reports. The third, from the pen of Warren Carter, Esq., was long and labored as an argument against altering the common version at all. In January, 1850, the majority report was unanimously adopted in these words:

'Resolved, That, in the opinion of this board, the sacred Scriptures of the Old and New Testament ought to be faithfully and accurately translated into every living language.'

'Resolved, That wherever, in versions now in use, known and obvious errors exist, and wherever the meaning of the original is concealed or obscured, suitable measures ought to be prosecuted to correct those versions, so as to render the truth clear and intelligible to the ordinary reader.

'Resolved, That, in regard to the expediency of this board undertaking the correction of the English version, a decided difference of opinion exists, and, therefore, that it be judged most prudent to await the instructions of the Society.'

On the publication of these resolutions the greatest excitement spread through the denomination. Most of its journals were flooded with communications, pro and con, sermons were preached in a number of pulpits denouncing the movement, and public meetings were held in several cities to the same end, notable amongst them one at the Oliver Street Church, in New York, April 4th, 1850. This feeling was greatly increased by the two following facts: Mr. Carter, an intelligent layman, but neither a scholar nor an able thinker, having submitted a learned and elaborate paper as his minority report, which occupied an hour in the reading, and believing that it was inspired by an astute author in New York who had opposed the Society from the first, and was then a member of the Board of the American Bible Society, Dr. Cone and William H. Wyckoff, President and Secretary of the American and Foreign Bible Society, published a pamphlet over their names in defense of the action of the board, under the title, 'The Bible Translated.' The second fact arose from the demand of Mr. Carter that those in favor of a revision of the English Scriptures should issue, in the form of a small edition of the New Testament, a specimen of the character of the emendations which they desired, in regard to obsolete words, to words and phrases that failed to express the meaning of the original Greek, or the addition of words by the translators, errors in grammar, profane expressions and sectarian renderings. Deacon William Colgate, the Treasurer, said that he approved of this suggestion, and that if Brethren Cone and Wyckoff would procure and issue such an edition as a personal enterprise, he, as a friend of revision, would personally pay the cost of the plates and printing. This was done, and in their preface they stated that by the aid of 'eminent scholars,' who had 'kindly co-operated and given their hearty approval to the proposed corrections,' they submitted their work, not for acceptance by the Society, but as a specimen of some changes which might be properly made, and that the plates would be presented to the Society if they were desired. This was sufficient to fan the fire to a huge flame; much stormy and uncalled for severity was invoked, and a large attendance was called for at the annual meeting to 'rebuke this metropolitan power' and crush the movement forever.

Men of the highest ability took sides and published their views, some demanding revision at once, others admitting its necessity but hesitating as to what might be the proper method to procure it, and still others full of fiery denunciation of Cone, Wyckoff and Colgate, and their sympathizers; as if they were guilty of the basest crime for desiring as good a version for the English speaking people as the Baptists were giving to the East Indians. Many others also talked as much at random as if they feared that the book which they hinted had come down from heaven in about its present shape, printed and bound, was now to be taken from them by force. From the abundant material before the writer a large volume might be submitted of the sayings and doings of many persons, of whom some are still living, and some have gone to their account with God; but as no good end can be secured at present by their reproduction they are passed in silence. It is much more grateful to refer to those more calm and thoughtful minds who stood unmoved in the storm, and, although they did not at that time see their way clear to aid the work of revision, yet spoke in a manner worthy of themselves as men of God in handling a great and grave subject, worthy of the Master whom they served, showing their consistency as defenders of our missionary versions. Pre-eminent amongst these was the late Dr. Hackett, who thus expressed himself May 2d, 1850:

'It is admitted that the received English version of the Scriptures is susceptible of improvement. During the more than 200 years which have passed since it was made, our means for the explanation, both of the text and the subjects of the Bible, have been greatly increased. The original languages in which it was written have continued to occupy the attention of scholars, and are now more perfectly understood. Much light has been thrown upon the meaning of words. Many of them are seen to have been incorrectly defined, and many more to have been rendered with less precision than is now attainable. The various collateral branches of knowledge have been advanced to a more perfect state. History, geography, antiquities, the monuments and customs of the countries where the sacred writers lived, and where the scenes which they describe took place, have been investigated with untiring zeal, and have yielded, at length, results which afford advantages to the translator of the Scriptures at the present day, which no preceding age has enjoyed. It is eminently desirable that we then have in our language a translation of the Bible conformed to the present state of critical learning.'

The Society met for its thirteenth anniversary in New York on the morning of May 22d, 1850. The crowd of life members, life directors and other delegates was very large, and the excitement rose as high as it well could. From the first it was manifest that calm, deliberate discussion and conference were not to be had, but that measures adverse to all revision were to be carried with a high hand. It had been customary to elect officers and managers before the public services; but, before this could be done Rev. Isaac Westcott moved: 'That this Society, in the issues of circulation of the English Scriptures, be restricted to the commonly received version, without note or comment;' and further moved that, as probably all minds were made up on the question, the vote should be taken without debate. Determined resistance to this summary process secured the postponement of the question to the afternoon, and other business was attended to. At that session each speaker was confined to fifteen minutes. Then in the heat of the Society it so far forgot the object of its organization as to vote down by an overwhelming majority the very principle on which it was organized. In the hope that, if revision could not be entertained, at least a great principle might be conserved as a general basis of agreement thereafter, the revisionists, on consultation, submitted the following: 'Resolved, That it is the duty of the Society to circulate the sacred Scriptures in the most faithful versions that can be procured.' When the Society had rejected this, and thus stultified itself, and denied not only its paternity but its right to exist by rejecting that fundamental principle, it was seen at a glance that all hope of its unity was gone. Yet, as a last hope that it might be saved, the following conciliatory resolution was submitted, but was not even entertained, namely:

'Whereas, Numerous criticisms of the learned of all denominations of Christians demonstrate the susceptibility of many improvements in the commonly received version of the English Scriptures; and whereas, it is deemed inexpedient for one denomination of Christians alone to attempt these improvements, provided the cooperation of others can be secured; therefore

'Resolved, That a committee of —— pious, faithful, and learned men, in the United States of America or elsewhere, be appointed for the purpose of opening a correspondence with the Christian and learned world, on all points necessarily involved in the question of revising the English Scriptures; that said committee be requested to present to the Society at the next annual meeting a report of their investigations and correspondence, with a statement of their views as to what revision of the English Scriptures it would be proper to make, if any; that until such report and statement shall have been acted upon by the Society the Board of Managers shall be restricted in their English issues to the commonly received version; and that all necessary expenses attendant upon this correspondence and investigation be paid by the Society.'

On the 23d, the following, offered by Rev. Dr. Turnbull, of Connecticut, was adopted:

'Resolved, That it is not the province and duty of the American and Foreign Bible Society to attempt, on their own part, or procure from others, a revision of the commonly received English version of the Scriptures.'

This action was followed by the election of the officers and the board by ballot, when Dr. Cone was re-elected President; but the Secretary, William H. Wyckoff, and the venerable Deacon Colgate, were proscribed, together with ten of the old managers, all known revisionists. No person then present can wish to witness another such scene in a Baptist body to the close of life. Dr. Cone, at that time in his sixty-sixth year, rose like a patriarch, his hair as white as snow. As soon as the seething multitude in the Mulberry Street Tabernacle could be stilled, he said, with a stifled and almost choked utterance: 'Brethren, I believe my work in this Society is done. Allow me to tender you my resignation. I did not withdraw my name in advance, because of the seeming egotism of such a step. I thank you, my brethren, for the kindly manner in which you have been pleased to tender me once more the office of President of your Society. But I cannot serve you longer. I am crushed.' The Society at first refused to receive his resignation, but, remaining firm in his purpose, it was accepted. When Messrs. Cone, Colgate and Wyckoff rose to leave the house in company, Dr. Cone invited Dr. Sommers, the first Vice-President, to the chair, remarking that God had a work for him to do which he was not permitted to do in that Society; and bowing, like a prince in Israel uncrowned for his fidelity, he said, amid the sobbing of the audience: 'I bid you, my brethren, an affectionate farewell as President of a Society that I have loved, which has cost me money, with much labor, prayer and tears. I hope that God will direct your future course in mercy; that we may do as much good as such creatures as we are able to accomplish. May the Lord Jesus bless you all.' Dr. Bartholomew T. Welch was chosen President, and Dr. Cutting Secretary of the American and Foreign Bible Society; then the body adjourned.

Spencer H. Cone, D.D., was, by nature, a man of mark, and would have been a leader in any sphere of life. He was born at Princeton, N J., April 13, 1785. His father and mother were members of the Hopewell Baptist Church. His father was high-spirited and fearless, noted for his gentlemanly and finished manners. He was an unflinching Whig, and fought with great bravery in the Revolution. Mrs. Cone was the daughter of Col. Joab Houghton. She possessed a vigorous intellect, great personal beauty, and an indomitable moral courage. Late in life, Dr. Cone loved to speak of the earnest and enlightened piety of his parents. When about fifty years of age he said in a sermon: 'My mother was baptized when I was a few months old, and soon after her baptism, as I was sleeping on her lap, she was much drawn out in prayer for her babe and supposed she received an answer, with the assurance that the child should live to preach the Gospel of Christ. The assurance never left her; and it induced her to make the most persevering efforts to send me to Princeton—a course, at first, much against my father's will. This she told me after my conversion; it had been a comfort to her in the darkest hour of domestic trial; for she had never doubted that her hope would be sooner or later fulfilled.' At the age of twelve he entered Princeton College as a Freshman, but at fourteen he was obliged to leave, when in his Sophomore year, in consequence of the mental derangement of his father and the reduction of the family to a penniless condition; they went through a hard struggle for many years. Yet the lad of fourteen took upon him the support of his father and mother, four sisters and a younger brother, and never lost heart or hope. He spent seven years as a teacher, first in the Bordentown Academy, having charge of the Latin and Greek department, and then he became assistant in the Philadelphia Academy under Dr. Abercrombie.

Spencer H. Cone, D.D., was, by nature, a man of mark, and would have been a leader in any sphere of life. He was born at Princeton, N J., April 13, 1785. His father and mother were members of the Hopewell Baptist Church. His father was high-spirited and fearless, noted for his gentlemanly and finished manners. He was an unflinching Whig, and fought with great bravery in the Revolution. Mrs. Cone was the daughter of Col. Joab Houghton. She possessed a vigorous intellect, great personal beauty, and an indomitable moral courage. Late in life, Dr. Cone loved to speak of the earnest and enlightened piety of his parents. When about fifty years of age he said in a sermon: 'My mother was baptized when I was a few months old, and soon after her baptism, as I was sleeping on her lap, she was much drawn out in prayer for her babe and supposed she received an answer, with the assurance that the child should live to preach the Gospel of Christ. The assurance never left her; and it induced her to make the most persevering efforts to send me to Princeton—a course, at first, much against my father's will. This she told me after my conversion; it had been a comfort to her in the darkest hour of domestic trial; for she had never doubted that her hope would be sooner or later fulfilled.' At the age of twelve he entered Princeton College as a Freshman, but at fourteen he was obliged to leave, when in his Sophomore year, in consequence of the mental derangement of his father and the reduction of the family to a penniless condition; they went through a hard struggle for many years. Yet the lad of fourteen took upon him the support of his father and mother, four sisters and a younger brother, and never lost heart or hope. He spent seven years as a teacher, first in the Bordentown Academy, having charge of the Latin and Greek department, and then he became assistant in the Philadelphia Academy under Dr. Abercrombie.

Prompted largely by the desire to support his mother and sisters more liberally, he next devoted seven years to theatrical life. He says: 'In a moment of desperation I adopted the profession of an actor. It was inimical to the wishes of my mother, and in direct opposition to my own feelings and principles. But it was the only way by which I had a hope of extricating myself from my pecuniary embarrassments.' he played chiefly in Philadelphia, Baltimore and Alexandria, and succeeded much better than he expected, but at times had serious misgivings about the morality of his associations and was greatly troubled about his personal salvation. In 1813 he left the stage, to take charge of the books of the 'Baltimore American.' A year later, he became one of the proprietors and conductors of the 'Baltimore Whig,' a paper devoted to the politics of Jefferson and Madison. At that moment the country had come to war with England, and he went to the field as captain of the Baltimore Artillery Company, under William Pinckney. He stood bravely at his post during the battles at Northpoint, Bladensburg and Baltimore, when shells tore up the earth at his feet and mangled his men at his side. During the war he married, intending to spend his time in secular life, but neglected the house of God. One day his eye dropped upon an advertisement of a sale of books, which he attended, and he bought the works of John Newton. On reading the 'Life of Newton,' his mind was deeply affected; he passed through agony of soul on account of his sins, which, for a time, disqualified him for business. His young wife thought him deranged, and having sought relief in various ways, at last he flew to the Bible for direction. He says:

'One evening after the family had all retired, I went up into a vacant garret and walked backwards and forwards in great agony of mind. I kneeled down, the instance of Hezekiah occurred to me, like him I turned my face to the wall and cried for mercy. An answer seemed to be vouchsafed in an impression that just as many years as I had passed in rebellion against God, so many years I must now endure, before deliverance could be granted. I clasped my hands and cried out, "Yes, dear Lord, a thousand years of such anguish as I now feel, if I may only be saved at last." . . . I felt that as a sinner I was condemned and justly exposed to immediate and everlasting destruction. I saw distinctly that in Christ alone I must be saved, if saved at all; and the view I had at that moment of Christ's method of saving sinners, I do still most heartily entertain after thirty years' experience of his love.'

Not long after this he began to preach in Washington, and so amazing was his popularity that in 1815-16 he was elected Chaplain to Congress. For a time he was pastor at Alexandria, Va., when he became assistant pastor in Oliver Street, New York, where he rose to the highest distinction as a preacher. The death of its minister, Rev. John Williams, left him sole pastor of that Church for about eighteen years, when he accepted the pastorate of the First Baptist Church, New York. For about forty years he was a leader in Home and Foreign mission work, and in the great modern movement for a purely translated Bible. In establishing our missions, many pleaded for the living teacher and cared little for the faithfully translated Bible, but he sympathized with Mr. Thomas, who, in a moment of heart-sorrow, exclaimed: 'If I had 100,000 I would give it all for a Bengali Bible.' he did much for the cause of education, but never took much interest in the scheme which associated Columbia College with the missionary field. In a letter to Dr. Bolles dated December 27, 1830, he wrote:

'The value of education I certainly appreciate, and think a preacher of the Gospel cannot know too much, although it sometimes unhappily occurs, to use the language of L. Richmond, that Christ is crucified in the pulpit between the classics and mathematics. Those missionaries destined, like Judson, to translate the word of God should be ripe scholars before this branch of their work is performed; but I am still of opinion that the learning of Dr. Gill himself would have aided him but little had he been a missionary to our American Indians.'

He was elected President of the Triennial Convention in 1832, and continued to fill that chair till 1841, when he declined a re-election. He had much to do with adjusting the working plans, first of the Triennial Convention and then of the Missionary Union. When the disruption took place between the Southern and Northern Baptists, in 1845, no one contributed more to overcome the friction and difficulties which were engendered by the new state of things and in forming the new constitution. Dr. Stow says:

'Concessions were made on all sides; but it was plain to all that the greatest was made by Mr. Cone. The next day the constitution was reported as the unanimous product of the committee. Mr. Cone made the requisite explanations, and defended every article and every provision as earnestly as if the entire instrument had been his own favorite offspring. The committee, knowing his preference for something different, were filled with admiration at the Christian magnanimity which he there exhibited. I believe he never altered his opinion that something else would have been better, but I never knew of his uttering a syllable to the disparagement of the constitution to whose unanimous adoption he contributed more largely than any other man.'

As a moderator, as an orator, as a Christian gentleman, he was of the highest order; he knew nothing of personal bitterness; he read human nature at a glance, and was one of the noblest and best abused men of his day. Like his brethren, he believed that the word 'baptize' in the Bible meant to immerse and that it was his duty to God so to preach it; but, unlike them, he believed that if it was his duty so to preach it, it was as clearly his duty so to print it; and therefor many accounted him a sinner above all who dwelt in Jerusalem. Of course, as is usual in all similar cases of detraction heaven has hallowed his memory, for his life was moved by the very highest and purest motives.

On the 27th of May, 1850, twenty-four revisionists met in the parlor of Deacon Colgate's house, No. 128 Chambers Street, to take into consideration what present duty demanded at their hands. They were: Spencer H. Cone, Stephen Remington, Herman J. Eddy, Thomas Armitage, Wm. S. Clapp, Orrin B. Judd, Henry P. See, A. C. Wheat, Wm. Colgate, John B. Wells, Wm. D. Murphy, Jas. H. Townsend, Sylvester Pier, Jas. B. Colgate, Alex. McDonald, Geo. W. Abbe, Jas. Farquharson, and E. S. Whitney, of New York city; John Richardson, of Maine; Samuel R. Kelly and Wm. H. Wykcoff, of Brooklyn; E. Gilbert, Lewis Bedell and James Edmunds, from the interior of New York. Dr. Cone presided, E. S. Whitney served as secretary, and Deacon Colgate led in prayer. For a time this company bowed before God in silence, then this man of God poured out one of the most tender and earnest petitions before the throne of grace that can well be conceived. T. Armitage offered the following, which, after full discussion, were adopted:

On the 27th of May, 1850, twenty-four revisionists met in the parlor of Deacon Colgate's house, No. 128 Chambers Street, to take into consideration what present duty demanded at their hands. They were: Spencer H. Cone, Stephen Remington, Herman J. Eddy, Thomas Armitage, Wm. S. Clapp, Orrin B. Judd, Henry P. See, A. C. Wheat, Wm. Colgate, John B. Wells, Wm. D. Murphy, Jas. H. Townsend, Sylvester Pier, Jas. B. Colgate, Alex. McDonald, Geo. W. Abbe, Jas. Farquharson, and E. S. Whitney, of New York city; John Richardson, of Maine; Samuel R. Kelly and Wm. H. Wykcoff, of Brooklyn; E. Gilbert, Lewis Bedell and James Edmunds, from the interior of New York. Dr. Cone presided, E. S. Whitney served as secretary, and Deacon Colgate led in prayer. For a time this company bowed before God in silence, then this man of God poured out one of the most tender and earnest petitions before the throne of grace that can well be conceived. T. Armitage offered the following, which, after full discussion, were adopted:

'Whereas, The word and will of God, as conveyed in the inspired originals of the Old and New Testaments, are the only infallible standards of faith and practice, and therefore it is of unspeakable importance that the sacred Scriptures should be faithfully and accurately translated into every living language; and,

'Whereas, A Bible Society is bound by imperative duty to employ all the means in its power to insure that the books which it circulates as the revealed will of God to man, should be as free from error and obscurity as possible; and,

'Whereas, There is not now any general Bible Society in the country which has not more or less restricted itself by its own enactments from the discharge of this duty; therefore,

'Resolved. That it is our duty to form a voluntary association for the purpose of procuring and circulating the most faithful version of the sacred Scriptures in all languages.

'Resolved. That in such an association we will welcome all persons to co-operate with us, who embrace the principles upon which we propose to organize, without regard to their denominational principles in other respects.'

On the 10th of June, 1850, a very large meeting was held at the Baptist Tabernacle in Mulberry Street, New York, at which the American Bible Union was organized, under a constitution which was then adopted, and an address explaining its purposes was given to the public. Dr. Cone was elected President of the Union, Wm. H. Wyckoff, Corresponding Secretary; Deacon Colgate, Treasurer; E. S. Whitney, Recording Secretary, and Sylvester Pier, Auditor, together with a board of twenty-four managers. The second article of the constitution defined the object of the Union thus:

'Its object shall be to procure and circulate the most faithful versions of the sacred Scriptures in all languages throughout the world.'

The address gave the broad aims of the Society more fully, and, among other things, said:

'The more accurately a version is brought to the true standard, the more accurately will it express the mind and will of God. And this is the real foundation of the sacredness of the Bible. Any regard for it founded upon the defects or faults of translation is superstition. In the consideration of this subject some have endeavored to poise the whole question of revision upon the retention or displacement of the word "baptize." But this does great injustice to our views and aims. For although we insist upon the observance of a uniform principle in the full and faithful translation of God's Word, so as to express in plain English, without ambiguity or vagueness, the exact meaning of baptize, as well as of all other words relating to the Christian ordinances, yet this is but one of numerous errors, which, in our estimation, demand correction. And such are our views and principles in the prosecution of this work that, if there were no such word as "baptize" or baptizo in the Scriptures, the necessity of revising our English version would appear to us no less real and imperative.'

While many men of learning and nerve espoused the movement, a storm of opposition was raised against it from one end of the land to the other. It expressed itself chiefly in harsh words, ridicule, denunciation, appeals to ignorance, prejudice and ill temper, with now and then an attempt at scholarly refutation in a spirit much more worthy of the subject itself and the respective writers. Every consideration was presented on the subject but the main thought: that the Author of the inspired originals had the infinite right to a hearing, and that man was in duty bound to listen to his utterances, all human preference or expediency to the contrary notwithstanding. After considerable correspondence with scholars in this country and in Europe, the following general rules for the direction of translators and revisers were adopted, and many scholars on both sides of the Atlantic commenced their work on a preliminary revision of the New Testament.

Dr. Conant proceeded with the revision of the English Old Testament, aided in the Hebrew text by Dr. Rödiger, of Halle, Germany.

The following were the general rules of the Union:

'1. The exact meaning of the inspired text, as that text expressed it to those who understood the original Scriptures at the time they were first written, must be translated by corresponding words and phrases, so far as they can be found in the vernacular tongue of these for whom the version is designed, with the least possible obscurity or indefiniteness.

'2. Whenever there is a version in common use it shall be made the basis of revision, and all unnecessary interference with the established phraseology shall be avoided, and only such alteration shall be made as the exact meaning of the inspired text and the existing state of the language may require.

'3. Translations or revisions of the New Testament shall be made from the received Greek text, critically edited, with known errors corrected.'

The following were the 'Special Instructions to the Revisers of the English New Testament:'

'1. The common English version must be the basis of the revision; the Greek text, Bagster & Son's octavo edition of 1851.

'2. Whenever an alteration from that version is made on any authority additional to that of the reviser, such authority must be cited in the manuscript, either on the same page or in an appendix.

'3. Every Greek word or phrase, in the translation of which the phraseology of the common version is changed, must be carefully examined in every other place in which it occurs in the New Testament, and the views of the reviser given as to its proper translation in each place.

'4. As soon as the revision of any one book of the New Testament is finished, it shall be sent to the Secretary of the Bible Union, or such other person as shall be designated by the Committee on Versions, in order that copies may be taken and furnished to the revisers of the other books, to be returned with their suggestions to the reviser or revisers of that book. After being re-revised, with the aid of these suggestions, a carefully prepared copy shall be forwarded to the Secretary.'

Amongst the scholars who worked on the preliminary revision in Europe were Revs. Wm. Peechey, A.M.; Jos. Angus, M.A., M.R.A.S.; T. J. Gray, D.D., Ph.D.; T. Boys, A.M.; A. S. Thelwall, M.A.; Francis Clowes, M.A.; F. W. Gotch, A.M., and Jas. Patterson, D.D. Amongst the American revisers were Drs. J. L. Dagg, John Lillie, O. B. Judd, Philip Schaff, Joseph Muenscher, John Forsyth, W. P. Strickland and James Shannon; Profs. E. S. Gallup, E. Adkins, M. K. Pendleton, N. N. Whiting, with Messrs. Alexander Campbell, Edward Maturin, Esq., E. Lord and S. E. Shepard. The final revision of the New Testament was committed to Drs. Conant, Hackett, Schaff and Kendrick, and was published 1865. The revisers held ecclesiastical connections in the Church of England, Old School Presbyterians, Disciples, Associate Reformed Presbyterians, Seventh-Day Baptists, American Protestant Episcopalians, Regular Baptists and German Reformed Church. Of the Old Testament books; the Union published Genesis, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, Job, Psalms and Proverbs; I and II Samuel, I and II Kings, I and II Chronicles, remaining in manuscript, with a portion of Isaiah. It also prepared an Italian and Spanish New Testament, the latter being prepared by Don Juan De Calderon, of the Spanish Academy. Also a New Testament in the Chinese written character, and another in the colloquial for Ningpo; one in the Siamese, and another in the Sqau Karen, besides sending a large amount of money for versions amongst the heathen, through the missionaries and missionary societies. It is estimated that about 750,000 copies of the newly translated or revised versions of the Scriptures, mostly of the New Testament, were circulated by the Union. Its tracts, pamphlets, addresses, reports and revisions so completely revolutionized public opinion on the subject of revision that a new literature was created on the subject, both in England and America, and a general demand for revision culminated in action on that subject by the Convocation of Canterbury in 1870.

As early as 1856 great alarm was awakened at the prospect that the American Bible Union would translate the Greek word 'baptize' into English, instead of transferring it, and the 'London Times' of that year remarked that there were already 'several distinct movements in favor of a revision of the authorized version' of 1611. The 'Edinburgh Review' and many similar periodicals took strong ground for its revision, and in 1858, Dr. Trench, then Dean of Westminster, issued an elaborate treatise showing the imperfect state of the commonly received version, and the urgent need of its revision, in which he said: 'Indications of the interest which it is awakening reach us from every side. America is sending us the installments—it must be owned not very encouraging ones—of a new version as fast as she can. . . . I am persuaded that a revision ought to come. I am convinced that it will come. The wish for a revision has for a considerable time been working among dissenters here; by the voice of one of these it has lately made itself known in Parliament, and by the mouth of a Regius Professor in Convocation.' The revision of the Bible Union was a sore thorn in his side; and in submitting a plan of revision in the last chapter, in which he proposed to invite the Biblical scholars of 'the land to assist with their suggestions here, even though they might not belong to the church,' of course they would be asked as scholars, not as dissenters, he adds: 'Setting aside, then, the so-called Baptists, who, of course, could not be invited, seeing that they demand not 'a translation of the Scripture but an interpretation, and that in their own sense.' Some Baptist writer had denied in the 'Freeman' of November 17, 1858, that the Baptists desired to disturb the word 'baptize' in the English version, but the Dean was so alarmed about their putting an 'interpretation' into the text instead of a transfer, that he said in a second edition, in 1859 (page 210): 'I find it hard to reconcile this with the fact that in their revision (Bible Union) baptizo is always changed into immerse, and baptism into immersion.' The pressure of public sentiment, however, compelled him to call for revision, for he said: 'However we may be disposed to let the subject alone, it will not let us alone. It has been too effectually stirred ever again to go to sleep; and the difficulties, be they few or many, will have one day to be encountered. The time will come when the inconveniences of remaining where we are will be so manifestly greater than the inconveniences of action, that this last will become inevitable.'

The whole subject came up before the Convocation of the Province of Canterbury in February, 1870, when one of the most memorable discussions took place that ever agitated the Church of England, in which those who conceded the desirableness of revision took ground; and amongst them the Bishop of Lincoln, that the American movement necessitated the need of prompt action on the part of the Church of England. In May of the same year the Convocation resolved: 'That it is desirable that Convocation should nominate a body of its own members to undertake the work of revision, who shall be at liberty to invite the co-operation of any eminent for scholarship, to whatever nation or religious body they may belong.'

The chief rules on which the revision was to be made were the first and fifth, namely:

'1. To introduce as few alterations as possible into the text of the authorized version consistently with faithfulness. 5. To make or retain no change in the text on the second final revision by each company, except two thirds of these present approve of the same, but on the first revision to decide by simple majorities.'

The revisers commenced their work in June, 1870, and submitted the New Testament complete May 17th, 1881, the work being done chiefly by seventeen Episcopalians, two of the Scotch Church, two dissenting Presbyterians, one Unitarian, one Independent and one Baptist. A board of American scholars had co-operated, and submitted 'a list of readings and renderings ' which they preferred to those finally adopted by their English brethren; a list comprising fourteen separate classes of passages, running through the entire New Testament, besides several hundred separate words and phrases. The Bible Union's New Testament was published nearly six years before the Canterbury revision was begun, and nearly seventeen years before it was given to the world. Although Dr. Trench had pronounced the 'installments' of the American Bible Union's New Testament 'not very encouraging,' yet the greatest care was had to supply the English translators with that version. During the ten and a half years consumed in their work, they met in the Jerusalem Chamber at Westminster each month for ten months of every year, each meeting lasting four days, each day from eleven o'clock to six; and the Bible Union's New Testament lay on their table all that time, being most carefully consulted before changes from the common version were agreed upon. One of the best scholars in the corps of English revisers said to the writer: 'We never make an important change without consulting the Union's version. Its changes are more numerous than ours, but four out of five changes are in exact harmony with it, and I am mortified to say that the pride of English scholarship will not allow us to give due credit to that superior version for its aid.' This was before the Canterbury version was completed, but when it was finished it was found that the changes in sense from the common version were more numerous than those of the Union's version, and that the renderings in that version are verbatim in hundreds of cases with those of the Union's version. In the March 'Contemporary Review,' 1882, Canon Farrar cites twenty-four cases in which the Canterbury version renders the 'aorist' Greek tense more accurately and in purer English than does the common version. He happily denominates all these cases 'baptismal aorists,' because they refer to the initiatory Christian rite in its relations to Christ's burial and resurrection. Yet, seventeen years before the Canterbury revisers finished their work, the Bible Union's version contained nineteen of these renderings as they are found in the Canterbury version, without the variation of a letter, while three others vary but slightly, and in the last case, which reads in the common version 'have obeyed,' and in the Canterbury 'became obedient,' it is rendered more tersely, in the Union's version, simply 'obeyed.'

Much as Dr. Trench was disquieted about the word 'immerse' being 'an interpretation' and 'not a translation of' baptizo, he was not content to let the word 'baptize' rest quietly and undisturbed in the English version, when compelled to act on honest scholarship, but inserted the preposition 'in' as a marginal 'interpretation' of its bearings, baptized 'in water.' Dr. Eadie, one of his fellow-revisers, who died in 1876, six years after the commencement of his work, complained bitterly of the American translation, which he was perpetually consulting in the Jerusalem Chamber. He also published two volumes on the 'Need of Revising the English New Testament,' and says (ii, p. 360): 'The Baptist translation of the American Bible Union is more than faithful to anti-Paedobaptist opinions. It professedly makes the Bible the book of a sect,' because it supplanted the word baptize by the word immerse. Yet, Dr. Scott, still another of the revisers, so well known in connection with 'Liddell and Scott's Lexicon,' worked side by side with both of them, and said in that lexicon that 'baptizo' meant 'to dip under water,' and Dean Stanley, still a third reviser, and the compeer of both, said: 'On philological grounds it is quite correct to translate John the Baptist by John the Immerser;' while the board of seventeen American revisers, representing the various religious bodies, united in recommending that the preposition 'in water' be introduced into the text, instead of 'with.'

After the separation between the American and Foreign Bible Society and the American Bible Union, the former continued to do a great and good work in Bible circulation and in aiding the translation of missionary versions. Dr. Welsh continued to act as its president for many years. For holy boldness, thrilling originality, artless simplicity and seraphic fervor, he was one of the marvelous preachers of his day, so that it was a heavenly inspiration to listen to his words. Both these societies continued their operations till 1883, with greatly diminished receipts, from various causes, and the Bible Union was much embarrassed by debt, when it was believed that the time had come for the Baptists of America to heal their divisions on the Bible question, to reunite their efforts in Bible work, and to leave each man in the denomination at liberty to use what English version he chose. With this end in view, the largest Bible Convention that had ever met amongst Baptists convened at Saratoga on May 22, 1883, and, after two days' discussion and careful conference, it was unanimously resolved:

'That in the translation of foreign versions the precise meaning of the original text should be given, and that whatever organization should be chosen as the most desirable for the prosecution of home Bible work, the commonly received version, the Anglo-American, with the corrections of the American revisers incorporated in the text, and the revisions of the American Bible Union, should be circulated.'

It also resolved:

'That in the judgment of this Convention the Bible work of Baptists should be done by our two existing Societies; the foreign work by the American Baptist Missionary Union, and the home work by the American Baptist Publication Society.'

Although the American Bible Union had always disclaimed that it was a Baptist Society, yet, a large majority of its life members and directors being Baptists, in harmony with the expressed wish of the denomination to do the Bible work of Baptists through the Missionary Union and the Publication Society, the Bible Union disposed of all its book-stock and plates to the Publication Society, on condition that its versions should be published according to demand. The American and Foreign Bible Society did the same, and now, in the English tongue, the Publication Society is circulating, according to demand, the issues of the Bible Union, the commonly received version and the Canterbury revision, with the emendations recommended by the American corps of scholars incorporated into the text; and so it has come to pass that the denomination which refused to touch English revision in 1850 came, in less than a quarter of a century, to put its imprint upon two, to pronounce them fit for use amongst Baptists, and to circulate them cheerfully.

Next to Dr. Cone, the three men who did more to promote the revision of the English Bible than any others, were Drs. Archibald Maclay, William H. Wyckoff, and Deacon William Colgate. Archibald Maclay, D.D., was born in Scotland in 1778, and in early life became a Congregational pastor there; but after his emigration to New York and a most useful pastorate there amongst that body he became a Baptist, moved by the highest sense of duty to Christ. For thirty-two years he was the faithful pastor of the Mulberry Street Church, and left his pastorate at the earnest solicitation of the American and Foreign Bible Society to become its General Agent. In this work his labors were more abundant than they had ever been, for he pleaded for a pure Bible everywhere, by address and pen, with great power and success. In Great Britain and in all parts of the United States and Canada he was known and beloved as a sound divine and a fervent friend of the uncorrupted word of God. At the age of eighty-two years, on the 22d of May, 1860, he fell asleep, venerated by all who knew him for his learning, zeal and purity.

William H. Wyckoff, LL.D., was endowed with great intellectual powers, and graduated at Union College in 1828. His early life was spent as a classical tutor, when he first became the founder and editor of the 'Baptist Advocate;' then, in turn, the Corresponding Secretary of the American and Foreign Bible Society and the American Bible Union. He served the latter until his death, at the age of three score and ten, in November, 1877, and his Secretaryship over these two bodies covered forty and two consecutive years.

Deacon William Colgate was one of the most consecrate and noble laymen in the Church of Christ, to whose memory such an able volume even as that of Dr. Everts, recounting the events of his life, can do but scant justice. He was born in Kent, England, in 1783, came to this country and established a large business in New York, which by his thrift and skill endowed him with abundant means for doing good. His elevated character and Christ-like spirit led him to the noblest acts of benevolence in the building up of Christian Churches, schools for the education of young ministers, the missionary enterprise and the relief of the poor. A pure Bible was as dear to him as his life, and few men have done more to give it to the world. He was the treasurer for numbers of benevolent societies, and one of the most liberal supporters of them all. He closed his useful and beautiful life on the 25th of March, 1857, at the age of seventy-four years.

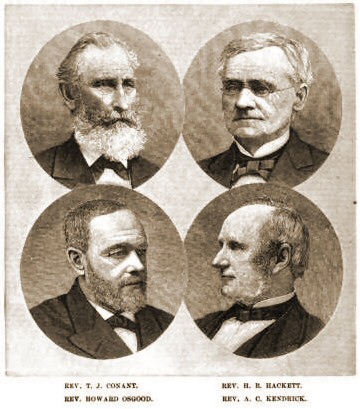

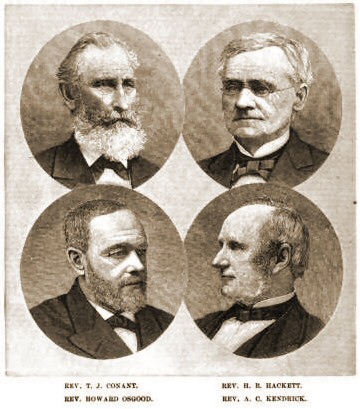

This chapter can scarcely be closed more appropriately than by a brief notice of four devoted Baptists, translators of the sacred Scriptures, in whose work and worth the denomination may feel an honest pride.

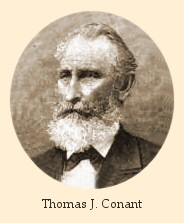

The veteran translator, Thomas J. Conant, D.D., was born at Brandon, Vt., in 1802. He graduated at Middleburg College in 1823, after which he spent two years, as resident graduate, in the daily reading of Greek authors with the Greek professor and in the study of the Hebrew under Mr. Turner, tutor in the ancient languages. In 1825 he became the Greek and Latin tutor in Columbian College, where he remained two years, when he took the professorship of Greek and Latin in the College at Waterville, where he continued six years. He then retired, devoting two years to the study of the Arabic, Syriac and Chaldee languages, availing himself of the aids rendered by Harvard, Newton and Andover. After this he accepted the professorship of Hebrew in Madison University, and that of Biblical Literature and Exegesis in the Theological Seminary connected therewith, in 1835. He continued these labors for fifteen years with large success and honor. In 1841-42 he spent eighteen months in Germany, chiefly in Berlin, in the study of the Arabic, Ethiopic and Sanscrit. From 1850 to 1857 he was the professor of Hebrew, Biblical Literature and Exegesis in the Rochester Theological Seminary, and stood in the front rank of American Hebraists with Drs. Turner and Stuart. Since 1857 Dr. Conant has devoted himself almost exclusively to the great work of his life, the translation and revision of the common English version of the Scriptures. He became thoroughly convinced as far back as the year 1827, on a critical comparison of that version with the earlier ones on which it was based, that it should be thoroughly revised, since which time he has made all his studies subsidiary to that end. Yet, amongst his earliest works, he gave to our country his translation of Gesenius' 'Hebrew Grammar,' with grammatical exercises and a chrestomathy by the translator; but his revision of the Bible, done for the American Bible Union, is the invaluable work of his life. This comprises the entire New Testament with the following books of the Old, namely: Genesis, Joshua, Judges, I and II Samuel, I and II Kings, Job, Psalms, Proverbs and a portion of Isaiah. Many of these are accompanied with invaluable critical and philological notes, and are published with the Hebrew and English text in parallel columns. His work known as 'Baptizein,' which is a monograph of that term, philologically and historically investigated, and which demonstrates its uniform sense to be immerse, must remain a monument to this distinguished Oriental scholar, while men are interested in its bearing on the exposition of Divine truth. Like all other truly great men, Dr. Conant is very unassuming and affable, and as much athirst as ever for new research. He keeps his investigations fully up with the advance of the age, and hails every new manifestation of truth from the old sources with the zest of a thirsty traveler drinking from an undefiled spring. In his mellowness of age, scholarship and honor, he awaits the call of his Lord with that healthy and cheerful hope expressed in his own sweet translation of Job 5:26: 'Thou shalt come to the grave in hoary age, as a sheaf is gathered in its season.'

The veteran translator, Thomas J. Conant, D.D., was born at Brandon, Vt., in 1802. He graduated at Middleburg College in 1823, after which he spent two years, as resident graduate, in the daily reading of Greek authors with the Greek professor and in the study of the Hebrew under Mr. Turner, tutor in the ancient languages. In 1825 he became the Greek and Latin tutor in Columbian College, where he remained two years, when he took the professorship of Greek and Latin in the College at Waterville, where he continued six years. He then retired, devoting two years to the study of the Arabic, Syriac and Chaldee languages, availing himself of the aids rendered by Harvard, Newton and Andover. After this he accepted the professorship of Hebrew in Madison University, and that of Biblical Literature and Exegesis in the Theological Seminary connected therewith, in 1835. He continued these labors for fifteen years with large success and honor. In 1841-42 he spent eighteen months in Germany, chiefly in Berlin, in the study of the Arabic, Ethiopic and Sanscrit. From 1850 to 1857 he was the professor of Hebrew, Biblical Literature and Exegesis in the Rochester Theological Seminary, and stood in the front rank of American Hebraists with Drs. Turner and Stuart. Since 1857 Dr. Conant has devoted himself almost exclusively to the great work of his life, the translation and revision of the common English version of the Scriptures. He became thoroughly convinced as far back as the year 1827, on a critical comparison of that version with the earlier ones on which it was based, that it should be thoroughly revised, since which time he has made all his studies subsidiary to that end. Yet, amongst his earliest works, he gave to our country his translation of Gesenius' 'Hebrew Grammar,' with grammatical exercises and a chrestomathy by the translator; but his revision of the Bible, done for the American Bible Union, is the invaluable work of his life. This comprises the entire New Testament with the following books of the Old, namely: Genesis, Joshua, Judges, I and II Samuel, I and II Kings, Job, Psalms, Proverbs and a portion of Isaiah. Many of these are accompanied with invaluable critical and philological notes, and are published with the Hebrew and English text in parallel columns. His work known as 'Baptizein,' which is a monograph of that term, philologically and historically investigated, and which demonstrates its uniform sense to be immerse, must remain a monument to this distinguished Oriental scholar, while men are interested in its bearing on the exposition of Divine truth. Like all other truly great men, Dr. Conant is very unassuming and affable, and as much athirst as ever for new research. He keeps his investigations fully up with the advance of the age, and hails every new manifestation of truth from the old sources with the zest of a thirsty traveler drinking from an undefiled spring. In his mellowness of age, scholarship and honor, he awaits the call of his Lord with that healthy and cheerful hope expressed in his own sweet translation of Job 5:26: 'Thou shalt come to the grave in hoary age, as a sheaf is gathered in its season.'

Howard Osgood, D.D., was born in the parish of Plaquemines, La., January, 1831. He pursued his academical studies at the Episcopal Institute, Flushing, N. Y., and subsequently entered Harvard College, where he graduated with honors in 1850, being marked for accurate scholarship, a maturity of thought and a sobriety of judgment. Subsequently, he became much interested in the study of the Hebrew and cognate languages under the instruction of Jewish scholars, which studies he also pursued in Germany for about three years. On his return to America, he became dissatisfied with the teachings of the Episcopal Church, to which he was then united, as to the Christian ordinances, and in 1856 he was baptized on a confession of Christ into the fellowship of the Oliver Street Baptist Church, New York, by Dr. E. L. Magoon. He was ordained the same year as pastor of the Baptist Church at Flushing, N. Y., which he served from 1856 to 1858, when he became pastor of the North Church, New York city, which he served from 1860 to 1865. He was elected professor of Hebrew Literature in Crozer Theological Seminary in 1868, where he remained until 1874, when he took the same chair in the Rochester Theological Seminary, which he still fills. He was appointed one of the revisers of the Old Testament (American Committee) and was abundant in his labors, his sagacity and scholarship being highly appreciated by his distinguished colleagues. He has written much on Oriental subjects, chiefly for the various Reviews; he is also the author of 'Jesus Christ and the Newer School of Criticism,' 1883; and of the 'Pre-historic Commerce of Israel,' 1885. He translated Pierret's 'Dogma of the Resurrection among the Ancient Egyptians,' 1885.