| Bible Research > English Versions > 19th Century > Rotherham |

New Testament, 1872. Joseph Bryant Rotherham, The New Testament: newly translated from the Greek text of Tregelles and critically emphasised, according to the logical idiom of the original; with an introduction and occasional notes. London: Samuel Bagster and Sons, 1872.

This is a very peculiar "literal" translation of the text of Tregelles 1857, with special markings to indicate untranslatable rhetorical emphasis. A portion of the work, The Gospel according to Matthew with Notes, had been published as a tentative issue in 1868. A revised second edition was published by Bagster in 1878. At least twelve printings of the complete New Testament were issued by Bagster between 1872 and 1893. A substantially revised edition of this version (commonly called "The Emphasised New Testament") was published by H.R. Allenson of London in 1897, as volume 4 of the complete Bible (see below).

Bible, 1897-1902. The Emphasised Bible: a new translation, designed to set forth the exact meaning, the proper terminology and the graphic style of the sacred originals: arranged to show at a glance narrative, speech, parallelism, and logical analysis, also to enable the student readily to distinguish the several divine names: and emphasised throughout after the idioms of the Hebrew and Greek tongues: with expository introduction, select references & appendices of notes. 4 volumes. London: H.R. Allenson, 1897-1902.

This edition was published beginning with the New Testament in volume 4 (1897), followed by the Old Testament in volumes 1-3 (1901-1902). An American edition of the New Testament portion was published by John Wiley & Sons of New York in 1897; and a one-volume American edition of the complete work was published in 1916 and thereafter by the Standard Publishing Company of Cincinnati. The New Testament translation in this edition is based on the text of Westcott and Hort instead of Tregelles.

Rotherham (1828-1910) was an Englishman and the son of a Methodist preacher. As a young man he began to follow in his father's path, and preached in various Methodist congregations, but he soon left the Methodists to join the Baptists, and then he departed from the Baptists also, to join the fellowship of congregations belonging to the "Restoration Movement" led by Alexander Campbell in the 1850's. He became an evangelist for the Campbellite Churches of Christ in 1854. In his Preface he states that his purpose was to aid a certain "class of Bible readers who were anxious above all things to get as near as possible to the simple, Apostolic (as distinguished from the mediaeval or modern) point of view from which to study the Christian Scriptures." The persons referred to here were the disciples of Campbell, who constantly emphasized the idea that true Christianity could be restored by rejecting all "traditions" of interpretation and studying the Bible alone.

The story of Rotherham's version is told in Reminiscences Extending Over a Period of More than Seventy Years, 1828-1906, by Joseph Bryant Rotherham, compiled with additional notes by his son, J. [Joseph] George Rotherham (London: H. R. Allenson, 1922).

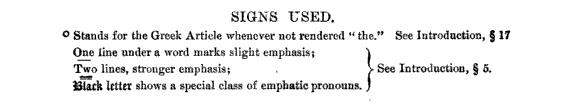

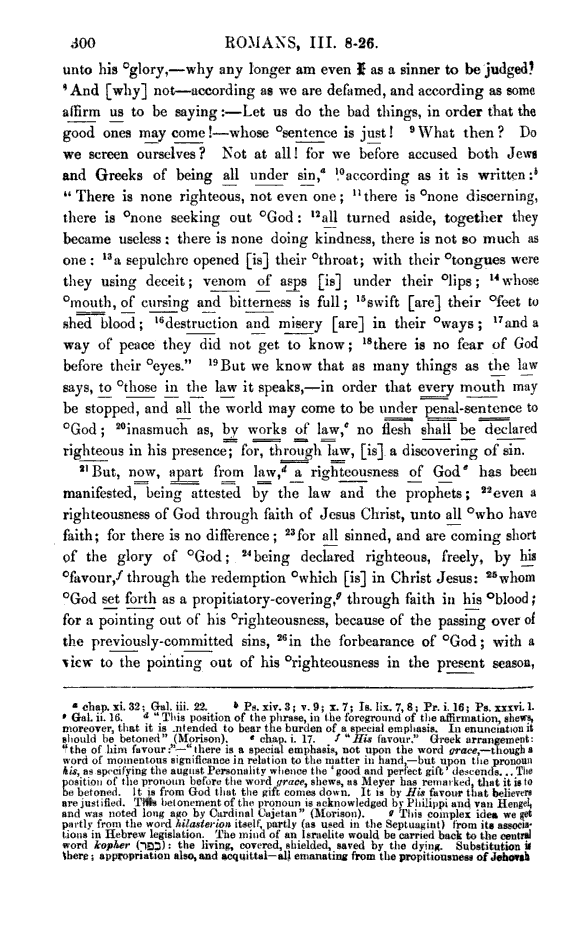

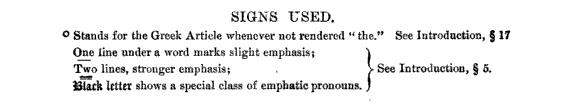

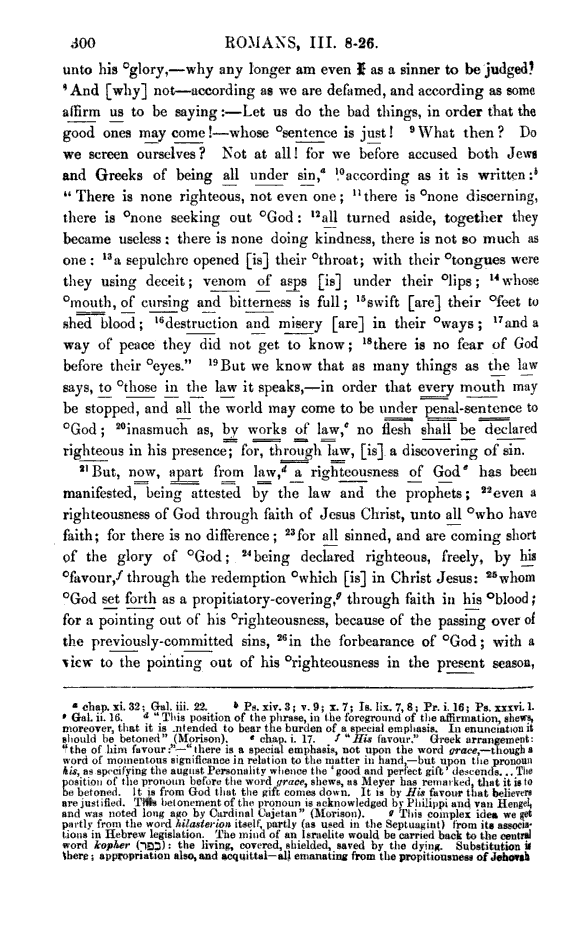

The version takes its name from the marks of emphasis that Rotherham added to the text, showing the rhetorical emphasis belonging to various words, based upon the word order and other features of the Greek text. Below we reproduce a page from the second edition of the New Testament (1878), showing his method in the first two editions.

In the revised edition of 1897 another method was used. Instead of the emphatic words being underlined, they were enclosed in vertical strokes or angle blackets to indicate various degrees of emphasis. The Introduction thoroughly explains how words receive emphasis in the Greek language.

As the page above also shows, Rotherham provided some interesting exegetical footnotes, supplemented by an appendix in which he discusses the meaning of many Greek words.

The translation itself is very difficult and peculiar, and indeed it can scarcely be called English. It resembles the kind of barbarous and occasionally absurd output one gets from translation software applications. The reason is, Rotherham produced the version in the same way that a computer would—he mechanically reproduced the order of the Greek words, no matter how unatural the result in English; he used the same English gloss for all occurrences of a Greek word, without any regard for contextual appropriateness; and he rendered the tenses of the Greek verbs into stereotyped English tenses, without any allowance for the differences between English and Greek grammar. He also did such things as refrain from using the English definite article "the" where the text did not have the Greek article, despite the fact that English usage does not correspond to Greek usage in this matter. Moreover, he seems to have had uninformed notions about the meaning of various Greek words, often preferring a 'root' meaning arrived at by some etymological fallacy. And so we see in the page above such renderings as "Why any longer am even I as a sinner to be judged;" (following the Greek word order); "do we screen ourselves" (giving an eccentric 'root' meaning to the Greek word); "a way of peace they did not get to know" (omitting the article, and attempting to represent the Greek aorist with a 'punctiliar' verbal tense in English), and so forth. Some flagrant examples of these tendencies to be found on other pages are:

Romans 8:31-32. "What, then, shall we say to these things? If God [is] for us, who [shall be] against us? 32 He, at least, who his own Son did not spare, but in behalf of us all delivered him up,—how shall he not also, with him, all things, on us, in favour bestow?"

Mark 7:1-4 "And the Pharisees and certain of the Scribes, who came from Jerusalem, are gathering themselves unto him; 2 and seeing certain of his disciples, that with profane hands, that is, unwashed, they are eating the loaves 3 (for the Pharisees and all the Jews, unless perchance with care they wash [their] hands, eat not;—holding fast the tradition of the elders. 4 And—from market—unless perchance they immerse themselves, they eat not. And many other things there are which they accepted to hold fast:—immersions of cups and measures, and copper [vessels], and couches), 5 and the Pharisees and the Scribes question him, For what reason are thy disciples not walking according to the tradition of the elders; but with profane hands are eating the loaf?"

The outlandish syntax of Romans 8:32 suggests to us one reason why "the humble countrywoman" mentioned by Rotherham in his Preface might have been "begging to have it read to her again and again," as he says. In Mark 7:4, we note especially the word "immerse" used for baptizo, which is an example of an etymological 'root' meaning being preferred over the actual meaning of the Greek word, as determined by context and usage. Rotherham regularly translates baptizo "immerse," and John the Baptist is even called "John the Immerser" in the version. (Needless to say, Rotherham held to the usual teaching of the Churches of Christ with regard to the mode of baptism.) The inappropriateness of "unless perchance" in verses 3 and 4, and of "the loaf" in verse 5, is also painfully obvious.

In the revised edition of 1897, there is some improvement in the translation of Mark 7:1-4.

"And the Pharisees and certain of the Scribes who have come from Jerusalem gather themselves together unto him; and observing certain of his disciples, that with defiled hands, that is unwashed, they are eating bread—for the Pharisees and all the Jews unless with care they wash their hands eat not, holding fast the tradition of the elders; and coming from market, unless they sprinkle themselves they eat not,—and many other things there are which they have accepted to hold fast,—immersions of cups and measures and copper vessels—"

This is certainly better. The word "perchance" has been dropped, and the Pharisees no longer "immerse themselves" before eating now. But "sprinkle" is substituted here only because Rotherham in this edition is translating from the Greek text of Westcott and Hort instead of Tregelles, and Westcott and Hort have here rantisontai instead of baptisontai. (Among critical editors of the text, only Westcott and Hort adopt this reading.) In a marginal note he again states that the alternative Greek reading is "immerse themselves," and thus he avoids recognizing that baptizo can mean "ritual washing" without immersion.

Regarding the other renderings mentioned above, only Romans 3:17 is improved somewhat in the edition of 1897, where it reads, "And way of peace have they not known" [sic]. But this is also unsatisfactory. It seems that Rotherham recognized that the indefinite article "a" did not belong before "way of peace" in his translation, but he still refuses to use the definite article "the," because he is determined not to use the definite article in English where there is none in the Greek. The result is a pointlessly ungrammatical rendering.

Problems like the ones pointed out here are very frequent in Rotherham's version of the Bible. It is quite obviously the work of an amateur, who began the work without much knowledge of the Greek language or of the cultural background of the New Testament, who adopted a rigidly mechanical procedure of translation (such as a school-boy might use), in which certain interlinear-style glosses are arbitrarily employed. It betrays in many places an insensitivity to the contextual meaning of Greek words and constructions. With its marks of emphasis, the version often does give accurate information about the emphasis belonging to Greek phrases, and it might be used for discovering that information while reading another version. But we cannot recommend the translation itself for any purpose.

THE special features of this New Testament may best be understood from a short statement of the design with which it was originally executed and is now again sent forth. The translator had been favoured to become acquainted with a class of Bible readers who were anxious above all things to get as near as possible to the simple, Apostolic (as distinguished from the mediaeval or modern) point of view from which to study the Christian Scriptures; and who were able, he believed, to use with thoughtfulness and care some more suitable means to this end than any public version, however excellent, could in the nature of things be. His purpose was to aid such readers as these.

It naturally grew out of this design, to translate from a purer Greek Text than the so-called Received; and further to adopt a style of Translation closer and less traditional than would otherwise have been proper. The fact that the now lamented Dr. S. P. Tregelles had devoted a life-time of faithful toil to the establishment of a Greek Text upon ancient authorities alone, led to the selection of his Text, in preference to that of Scholz, Tischendorf, or any other scholar, as being wholly congenial with the special object the translator had in view; and, having made this choice, it was the plainest dictate of respect for the judgment of this distinguished scholar to follow his guidance implicitly in all matters affecting the exact wording of the Sacred Original.

It is important, however, to bear well in mind the clear distinction between Greek readings and English renderings. It is one thing to determine what Greek ought to be preferred, and manifestly quite another to settle and apply the principles on which, when chosen, it shall for any given purpose be represented in English. This distinction precisely indicates where relative responsibility begins and ends. In the present case, the translator was glad to feel no responsibility whatever as to the Greek Text, beyond that of deciding what Editor to follow; but, on the other hand, the entire responsibility of conceiving and executing this version rests on the translator alone. It would be unjust to allow it to be supposed that either Dr. Tregelles or his friends were in any way concerned in the production of this work, especially seeing that, while extremely literal, it departs considerably from the beaten track. It is true that some of the most striking results discoverable in the following pages are directly owing to variations in the original; but, more often than not, it is the reverse, and the difference is due to the individual judgment of the translator in dealing with the text before him and resorting for the sake of exactness to unwonted forms of rendering.

This last statement reminds the translator of the weight of his own burden, from which, he now takes leave to say, he has seen no good cause to shrink. He intended from the first to go considerably beyond merely giving the results of what is commonly termed textual criticism. He sought to give distinct help to such as wished to come to the Apostolic Writings with as little conventionalism as possible. His conviction that there was such a class, sufficiently large to claim regard, has been happily confirmed by the acceptance given to this work. From the scholar, using it for comparison in his own reading of the original; from the missionary, giving it welcome as a help among the heathen; from the village preacher, telling of the flood of light thrown by it on the Good News of God as set forth in the great Epistle to the Romans; even from the humble countrywoman, begging to have it read to her again and again; from these and such as these have testimonies come, proving that the translator's labour has not been altogether in vain. It is simple gratitude to say this.

A suitable return has been attempted in the improvements introduced into this second edition. The entire text of the translation has been subjected to a careful revision; and the idiom has been cautiously softened, here and there, where it could be done without material loss of exactness.

In cases of importance, the readings of the Sinai MS. have been given, at the foot, throughout the Gospels ; as this part of the Greek Text had not, when printed, received the advantage of a comparison with this famous and venerable copy. A collation of the results previously arrived at with the Sinai readings will interest many.

As the Greek Editor had sometimes set down one reading in his text and another in his margin, in deference to nearly a balance of evidence, it was felt to be more scrupulously fair to him to give some indication of this fact in translation. Accordingly a selection of such "alternative readings" will here be found, although of course only in English. In no case has any attempt been made to show what the evidence is for or against text or margin. Results only have been dealt with: it appeared best to say precisely how.

Various minor improvements introduced into this Edition will be obvious at a glance; such as the greater neatness of the underscored lines, the addition of a series of select references, and the division of the Gospels and Acts into sections with headings and parallels. The Epistles have been left unbroken, inviting repeated perusal from end to end at a sitting. Finally, the Introduction has been wholly rewritten, to adapt it to wider and more practical usefulness. Containing now the pith of the scattered notes on Emphasis given in the First Edition, room has been made for the references and for some additional notes. The critical explanations attached to the new Introduction will make plain to the Scholar the exact principles on which this Translation has been emphasised, and the slight modifications which further study has induced.

LONDON, 1878.

| Bible Research > English Versions > 19th Century > Rotherham |